Every day, you carry about a nickel’s worth of copper in your pocket. Ironically, this has nothing to do with how many coins you have, especially since the penny hasn’t been made of pure copper since 1982.

Instead, think of the piece of tech that nearly every human in the civilized world carries: a cell phone. The modern mobile phone contains about six grams worth of copper. At today’s price of $0.25 per ounce, this works out to be around $0.05.

This might not sound impressive until you consider the sheer number of applications for copper today and its strategic importance for the American economy.

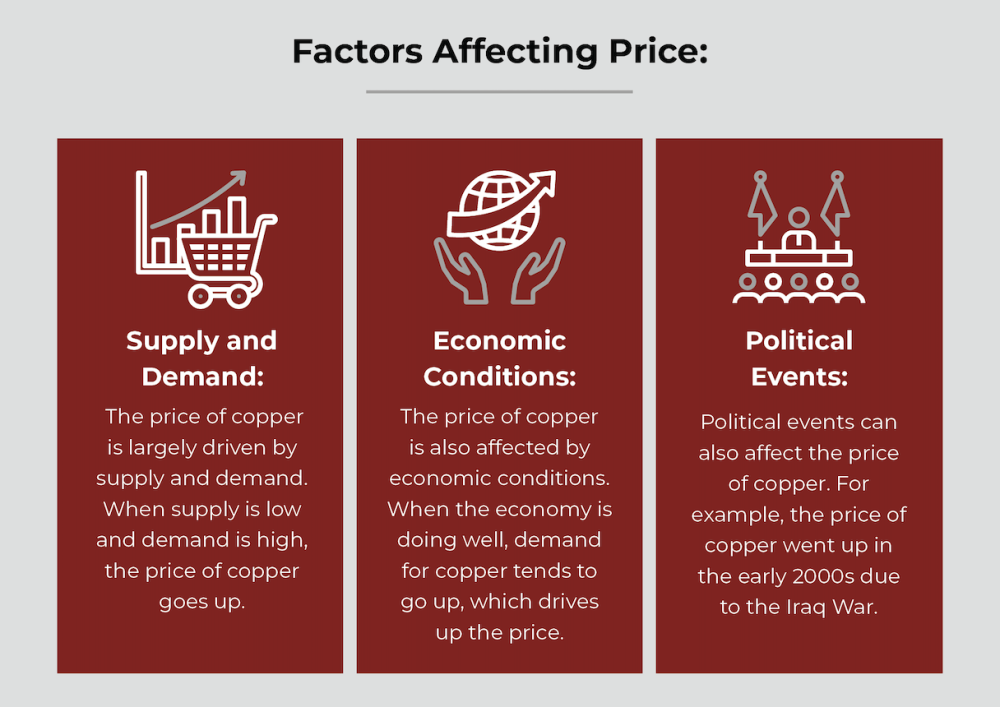

How has the cost of copper changed over time? Well, like most commodities, the price of copper is determined by the balance between supply and demand. For copper, specifically, these factors have been heavily influenced by the development of new consumer technologies, new manufacturing processes, and economic models.

The following discussion explores the way these trends have influenced the price of copper over the centuries and gives consideration to trends that will influence the cost in the near future.

What Is Copper?

First, it might help to get a little background on the element itself. In its native form, copper is known for its orange-brown coloration and is one of the few metallic elements to have a natural color other than gray or silver.

The name itself derives from the region of Cyprus, the principal mining area during the Roman empire. From Cyprus, we get the Latin name “Cuprum,” from which the chemical symbol for copper is derived — Cu.

Copper is abundantly found in the earth’s crust and readily binds with other elements and compounds. Copper is also one of few metallic elements that can be used in its native form. Copper’s malleability makes it easy to bend and work with, and it’s also a well-known conductor of heat and electricity.

Why Is Copper So Valuable?

Unlike other metallic elements (such as gold), copper is not valued for its scarcity but for its utility. Due to its malleability, copper has been frequently used in the construction of boats, buildings, and tools. Even today, it remains a staple of the construction industry. In fact, its antimicrobial properties make it ideal for frequently-touched surfaces such as handrails.

Its unusual coloration likewise has made it an interesting design element for art and architecture. Copper is known for developing a characteristic green patina, which is what gives the Statue of Liberty its distinctive color.

In the industrial age, copper is valued for its ability to conduct electricity. Roughly 60% of the copper in use today is found in the electrical wiring of residential and commercial architecture. Copper is also found in electrical devices, and it’s even a major component in modern cars.

Where Does Copper Come from?

Copper can be found just about anywhere in the world. In order for copper to be used, it must be extracted, purified, and refined.

Chile is the largest producer of copper, followed closely by Peru. The United States is the second-largest producer of copper, with major mines in Arizona, Michigan, New Mexico, and Montana.

In the eastern hemisphere, copper is frequently mined in certain parts of Russia and several countries in Africa.

The History of Copper Demand: From the Prehistoric to the Modern Era

Copper has a rather lengthy history, and it may be helpful to survey the way that copper was used (and valued) in the centuries leading up to the modern era.

The Prehistoric Period

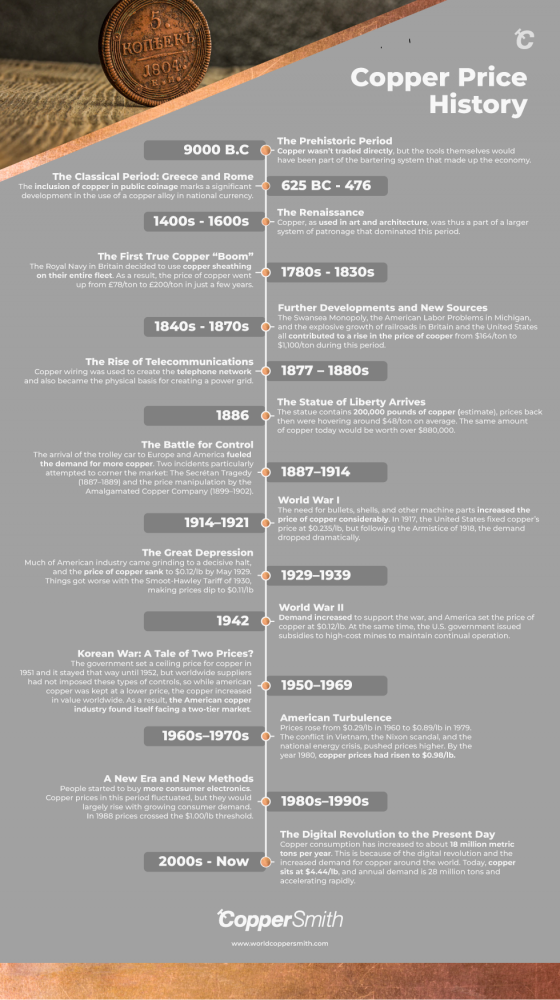

The use of copper dates all the way back to 9000 B.C. when copper was used for making jewelry in the Middle East. Copper tools were also prominent in the Neolithic period (around 7500 B.C.), and over time, these copper materials were blended with other materials such as wood and stone.

This means that copper would have been blended into the period known as the “bronze age.” Other sources indicate that Egypt used copper to develop a rudimentary plumbing system.

Assessing the value of copper during this period is difficult, given its scarcity. It’s likely that copper wasn’t traded directly, but the tools themselves would have been part of the bartering system that made up the economy.

The Classical Period: Greece and Rome

Technologically speaking, there was not much further development during the Greco-Roman era, though copper was still a major part of the process of making tools and weapons. In other parts of the ancient world, copper was being used to develop surgical instruments, and copper compounds were also being used to treat and sterilize wounds.

What makes the era distinct is the inclusion of copper in public coinage under Octavianus Augustus Caesar in the early years of the first century A.D. This marks a significant development in the use of a copper alloy in national currency.

The Renaissance

Fast forward to the era of the Renaissance, and you’ll begin to see copper included in many forms of art and architecture. Its distinctive patina made copper a coveted building material, commonly used in roofs.

During this period, artistic works were frequently commissioned by the wealthy elite, including churches. Copper, as used in art and architecture, was thus a part of a larger system of patronage that dominated this period.

The First True Copper “Boom” (1780s–1830s)

The first major copper “boom” occurred in the 1780s when Britain’s Royal Navy chose to re-hull their entire fleet using copper sheathing. Covering their hulls with metal protected against shipworm, seaweed, and other forms of mechanical stress. Additionally, it gave their ships a competitive advantage during the Napoleonic Wars, as sheathed vessels were faster and required less maintenance.

As a result, copper prices rose from £78/ton in 1785 to £200/ton in 1807. Adjusting for inflation, this is the modern equivalent of £20,470 ($24,850) per ton. But in reality, today’s copper costs an average of $9,322/ton, showing just how much this demand drove up the price in a relatively short period of time.

This first boom proved to be short-lived because of two distinct developments:

- The demand for copper promoted overseas mining operations in countries such as Chile

- Zinc/copper alloys (Muntz metal) replaced pure copper on boat sheathing

These developments destabilized the copper market, driving prices down to a more reasonable £85/ton ($103/ton) by 1830.

Further Developments and New Sources (1840s–1870s)

By the early part of the nineteenth century, America was a well-established player on the world stage. In some ways, the California Gold Rush had diverted attention away from other mining efforts, but there were several key developments that had a direct impact on the copper industry.

Railroads (1840s–1850s)

During the 1840s, Britain experienced an explosive growth of railways, which increased the demand for copper for boilerplates and other mechanical fixtures. By the 1850s, London reported copper prices as high as £135/ton ($164/ton), coinciding with the Crimean War.

Michigan Mining Operations (1840s–1850s)

The United States also saw increased demand for copper during the era of the railroad. Fortunately, in 1837, Michigan was adopted as the 26th state. Within a few years, 400-ton boulders of native copper were discovered in the northern part of the state, greatly increasing the copper supply.

The Swansea Monopoly (1850s–1860s)

Global copper prices rose during this time, in part because of the arrival of the Associated Smelters of Swansea. This organization quickly became the world’s first copper producer cartel.

Not only did their smelters process the bulk of the world’s copper ore, but they used a proprietary technique known as the “Welsh Process” that soon dominated the industry. These factors gave them control over the world’s copper supply, effectively allowing the company to dictate the price of their refined copper.

The Civil War (1860s)

Initially, Michigan mining operations in the Lake Superior region meant that American manufacturers could obtain copper for as low as $0.17/pound. But the Civil War would change that, causing another dramatic spike in price the same way that Britain’s Napoleonic Wars had.

The Union, for example, relied on copper for canteens, cannons, and buttons on their uniforms. As a result, the price of Lake Superior Ingot rose to $0.55/pound, more than triple its starting value.

American Labor Problems (1860s)

Until the 1860s, the relationship between supply and demand had been a relatively simple one, and the discovery of the Lake Superior Ingot had been a stroke of luck. But as the price of copper increased, Michigan miners began to demand higher pay, straining the relationships between workers and their supervisors.

Many mine owners simply chose to replace their workforce with foreign labor, including workers from Cornwall, Wales, and Scandinavia. At the same time, a new smelting process (the Bessemer process) vastly boosted the efficiency and output of mining operations. This would also mean that the stranglehold the Swansea Association had over the copper industry had come to a decisive end.

The Rise of Telecommunications (1877–1880s)

The impact of the rise of telecommunications can’t be overstated. In many ways, western culture had not seen a revolution of this magnitude since the arrival of the printing press in 1453.

The telegraph was invented back in 1837, and it had already made a considerable cultural impact. For the first time, people were able to send information across great distances with virtually no delay. But the most dramatic advancement came in 1876 with the arrival of the telephone.

Telegraph wires were previously composed of iron, but Thomas Doolittle, a brass mill man from Connecticut, developed a phone wire system that relied on copper. The effects were as dramatic as they were immediate. Within a surprisingly short time, copper wiring was used to create the telephone network and also became the physical basis for creating a power grid.

Copper had previously been used in the development of tools, architecture, coins, and other tangible commodities. But now, almost miraculously, copper would serve to bring national unity on a scale previously unthinkable. The copper industry grew at a rate of 5.8% as more cities adopted these telecommunications methods and powered their cities.

The Statue of Liberty Arrives (1886)

No history of copper could possibly be complete without acknowledging the Statue of Liberty. Conceived as a joint project between America and France, America would build Lady Liberty’s pedestal, while France would supply the famous copper sculpture that rests upon it.

The idea behind the project dates back to 1865, the close of the American Civil War. But construction did not begin in earnest until 1876. On October 28, 1886, President Grover Cleveland dedicated the statue, to the applause of thousands of spectators.

By most estimates, the statue contains 200,000 pounds of copper, though it’s difficult to determine the exact amount. If we assume that copper prices were hovering around $48/ton on average (which, again, is difficult, given the turbulence of the industry during this era), the raw materials alone would be worth $4,800.

That might not sound impressive, but the same amount of copper today would be worth over $880,000. But the real value of the statue, of course, is symbolic. Only copper could provide the green patina that characterizes this statue as Lady Liberty welcomes immigrants into New York Harbor.

The Battle for Control (1887–1914)

Though copper prices had begun to fall in 1882, demand for copper ran high in the latter years of the eighteenth century. In addition to the advent of telecommunications, Europe and America had witnessed the arrival of the trolley car. Together, these technological leaps would only fuel the demand for more copper.

That also meant that there were multiple attempts to “corner the market,” so to speak. Two incidents are particularly worth highlighting.

The Secrétan Tragedy (1887–1889)

In 1887, Pierre Secrétan, the owner of the largest copper fabricator in Europe, controlled over 80% of the world’s copper supply. He single-handedly pushed copper prices up by 150%, making this one of the largest attempts at cornering the market to date.

Secrétan began buying bars of copper in the Fall of 1887. At that time, he paid a price of £40/ton ($48/ton), which, by some estimates, is the equivalent of $1,000 or more today. At the same time, he seized control of 80% of the world’s mines by offering them a price of £68/ton over a period of three years. By the next year, the price of copper had risen to £85/ton ($103/ton).

What Secrétan never counted on was the ability of primary producers to use recycled copper. Broken items were converted back into ingots, which decreased Secrétan’s hold on the worldwide copper industry. Soon, the company was facing a surplus of materials, causing significant strain on the company. Tragically, a secretary of one of the backing banks committed suicide. When the news spread, the price of copper dropped to £35/ton ($43/ton) overnight.

Not to be outdone, Secretan’s other backers began flooding the market with copper. This triggered a war between miners and producers, forcing the backing banks to agree to sell the backlog slowly over a period of four years. As a result, copper prices dropped to around £36/ton ($44/ton) for six years. Prices would not rise again until the demands of the electrical grid could outpace the excess supply.

Amalgamated Copper Company (1899–1902)

The Secrétan tragedy was not soon forgotten. It wasn’t until April 1899 that Standard Oil sought to corner the market by establishing the Amalgamated Copper Company. The company held a controlling stake in the largest copper mine in Butte, Montana, and slowly phased out U.S. production in favor of European production and export.

Initially, prices soared. Amalgamated was only able to maintain its grip by buying up independent producers, which it did at no small expense. Soon, the company decided to deliberately drive down the price of copper to put independent producers out of business. By 1901, Amalgamated had driven copper prices to a mere $0.105/lbs.

But this backfired. The independent companies held out, refusing to sell until the market improved. While they waited, Amalgamated couldn’t sustain the low prices they’d artificially created, forcing them to hike the price back to $0.15/lbs.

Now that the market had restabilized, independents were able to regain a foothold in the copper market, spurred on by the continual, rapid growth of electricity.

World War I and Increased Copper Demand (1914–1921)

Following these earlier attempts at establishing a copper monopoly, prices largely stabilized. It wouldn’t be until the first Great War that another major spike in demand would boost the copper industry. The need for bullets, shells, and other machine parts increased the price of copper considerably.

With struggling production and speculative buying, the European government stepped in and set a price for copper. In 1917, the United States fixed copper’s price at $0.235/lb.

Likewise, the dramatic increase in demand prompted warring nations to pursue alternative sources of copper supply. This included things like:

- New overseas sources in places like Rhodesia

- New mining techniques that allowed the use of lower-grade ores

- Recycled scrap metal collected from the battlefield

During the years of the war, the race to keep the supply chain moving was an ongoing effort. But following the Armistice of 1918, the demand dropped dramatically. The United States, as well as other nations, ended their price control, and prices dropped dramatically now that the supply far exceeded the peacetime demand.

Stateside, demand built as manufacturers and builders delayed production until the war was over, which caused a slight resurgence from 1919 to 1920. But following this brief bubble, prices once again stabilized, resulting in a drop in value that would continue into one of the gloomiest periods in American history — the Great Depression.

Copper Prices in the Great Depression

Great Depression (1929–1939)

During the Great Depression, much of American industry came grinding to a decisive halt. That meant that the demand for many materials had been all but extinguished, including copper and steel.

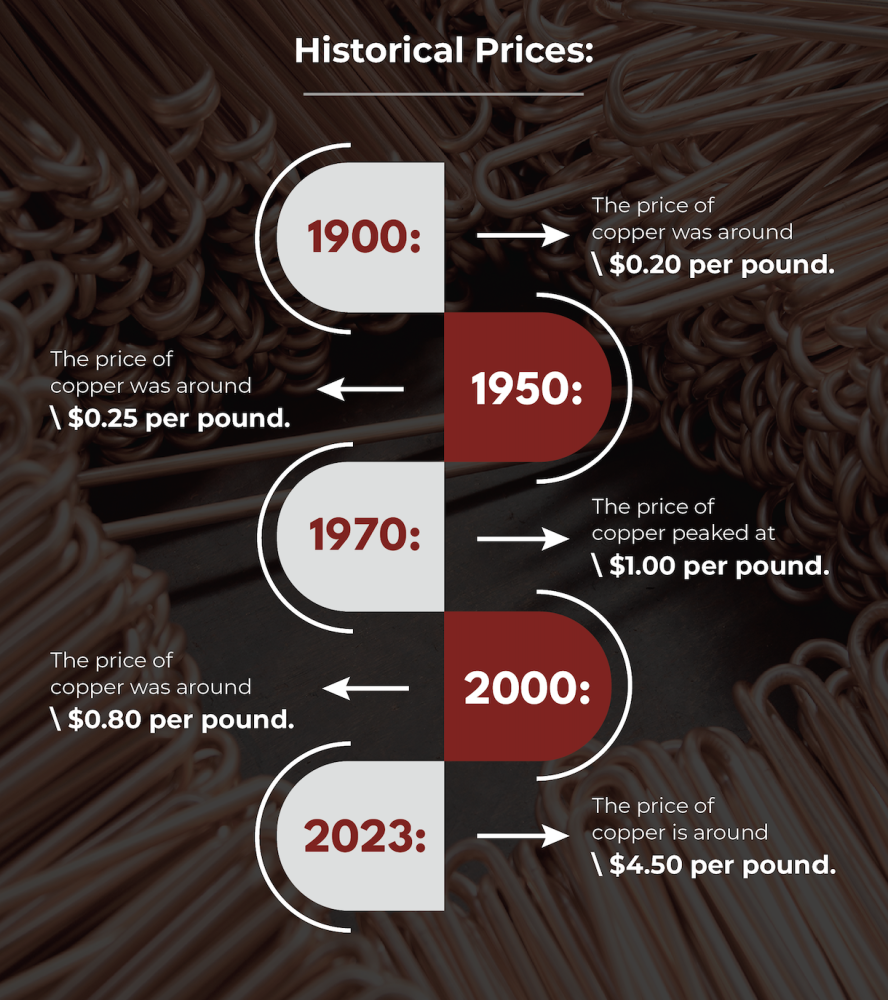

What’s more, the United States was still dealing with the ripple effects of the wartime surplus. Basically, the ratio between supply and demand had become completely distorted, and the price of copper sank to $0.12/lb by May 1929.

Things would only get worse with the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930. In principle, it made sense to raise import duties to protect American industries and farmers. But it also caused European countries to cancel their orders of copper and other non-ferrous metals. Soon, copper dipped to $0.11/lb.

Some commodities companies made attempts to set prices. Even some copper cartels tried to set a price at $0.12/lb. But these efforts proved unsuccessful as the price of many consumer goods and commodities stagnated.

Copper Prices Surged in World War II

Just as the first Great War triggered a renewed demand for copper, World War II brought a rise in demand in support of the war. But unlike during the previous war, the government chose to set the price from the outset to avoid instability in the supply and price of commodities.

In 1942, America set the price of copper at $0.12/lb. At the same time, the U.S. government issued subsidies to high-cost mines to maintain continual operation. It wasn’t quite the same boon as in World War I, but it nonetheless represented a calculated response to increased demand.

Immediately after the war, these price controls were ended, though the market did not experience a dramatic fluctuation just yet. But the clouds of war had now lifted, which means that America was free to enter a period of relative optimism in the years just prior to the Korean War.

This new outlook gave rise to an increase in domestic manufacturing, housing, and more as Americans looked to the future with hope. In the short period following World War II, copper remained in demand even after price controls were lifted. This didn’t cause a significant boost in prices, but it nonetheless ensured that the industry would not suffer a dip in the aftermath of war efforts.

Korean War: A Tale of Two Prices? (1950–1969)

Any concern that the commodities sector would see a drop in the decade following World War II would be dashed by the onset of the Korean War. By January of 1951, the U.S. government set a ceiling price of $0.246/lb on all domestic copper.

The price control remained active until the end of 1952. While this was hardly the first time that America had imposed such a price control, this time, there was a problem: Other worldwide suppliers had not imposed these types of controls.

So while American copper was kept at a lower price, the copper increased in value worldwide. Even after the price control was lifted, American copper prices remained lower than other worldwide producers.

As a result, the American copper industry found itself facing a two-tier market. There would be a completely different price for U.S. consumers and a different price for other international producers. This price disparity would last for years, not ending until the close of the 1960s. By that time, the price for U.S. producers was around $0.30/lb, while international prices had risen to $0.50/lbs. This meant that U.S. prices were around 40% less than the prices of copper around the world.

Meanwhile, the copper industry faced another critical challenge: the pressure to replace copper wiring with cheaper alternatives, such as aluminum. Aluminum wiring was considerably cheaper, and it allowed builders to complete construction more rapidly than before. But copper proved to be the stronger metal, and copper producers were not routed by the demand for cheaper materials.

American Turbulence Pushes Prices Higher (1960s–1970s)

The data from the years 1960 to 1979 indicates a noticeable upward curve in copper prices, rising from $0.29/lb in 1960 to $0.89/lb in 1979.

It’s easy to understand how the turbulence of this time period pushed copper prices higher and higher. Like past wars, the conflict in Vietnam led to stockpiling in the United States. Later, the Nixon scandal and national energy crisis would serve to push prices even higher.

In the late 1960s, the native copper reserves of Michigan had finally been exhausted. By that point, the industry had removed roughly 10.5 billion pounds of copper from the area, and further mining efforts were no longer profitable. Later, in 1992, President George H.W. Bush would establish Keweenaw National Historical Park to preserve the region’s history, geology, and culture, thereby eliminating any potential for further profit.

By the year 1980, copper prices had risen to $0.98/lb. By then, America’s turbulence had largely subsided, and a new era was about to dawn.

A New Era and New Methods (1980s–1990s)

The 1980s saw several new developments in the copper industry, each of which had a distinct effect on the price.

A New Method (Early 1980s)

Historically, copper had to be mined from high-quality sources in order for it to be useful and valuable. Naturally, this created limits for copper miners and producers, which tended to create an increase in price.

The 1980s saw a rise in the popularity of modern heap-leach technology. This method had been around for years already, but it hadn’t been applied to large-scale copper mining until after 1980.

As a result, larger copper deposits in South America became available, increasing the worldwide supply of copper. From 1980 to 1985, prices dropped from $0.98/lb to $0.61/lb.

New Regulations (1980s)

While the Environmental Protection Agency had been established under Nixon in the previous decade, it was in the 1980s when the mining industry fell under greater environmental scrutiny.

One of the byproducts of mining is something called “poor rock,” which refers to rocks that are crushed and discarded once the valuable copper has been extracted. At major mining centers, poor rock was polluting waterways and littering fields. In Torch Lake, fish developed cancerous tumors from the 200 million tons of mining waste.

In 1986, the federal government established a Superfund site to protect and rehabilitate lakes where companies had dumped hazardous waste into the waters. This would be the start of an increased focus on environmental concerns, a trend that continues into the present day.

New Demands (Late 1980s–1990s)

An economic recession had depressed commodity prices in the earlier part of the 1980s, but the end of this recession would roughly coincide with the rise of consumer electronics in the latter half of the decade.

Technologies like stereo systems, televisions, and household computers were increasingly becoming the norm, a trend that would solidify into the 1990s as the internet burst in popularity.

Copper prices in this period fluctuated, but they would largely rise with growing consumer demand. Prices crossed the $1.00/lb threshold in 1988 and would remain above this mark for most of the next ten years.

The Digital Revolution to the Present Day

According to the United States Geological Survey, copper consumption has risen to roughly 18 million metric tons per year. This is due largely in part to the digital revolution of the last few decades, as well as increased global demands.

Though commodities prices have fluctuated since 2000, there’s been a strong upward trend since 2006. Today, copper sits at $4.44/lb, and annual demand is 28 million tons and accelerating rapidly.

Stateside, the Trump and Biden administrations have brought renewed focus on building American infrastructure. But there are two broader, global trends that are impacting today’s copper industry.

Growing Global Demand

Other countries have long been consumers of copper and other commodities. But since 2006, China and India have accelerated their growth in the technology and transportation sectors. China in particular began pushing for megacities and high-speed rail networks, hence the sudden, dramatic demand for copper.

By 2008, China accounted for nearly a quarter (22%) of the worldwide copper demand, and today it’s estimated that half of the demand comes from China alone. In recent years, China has turned to allies in the Arab world to meet their needs, but the rate at which they are consuming is still causing strain on the worldwide network of copper producers.

Recycled Materials

A study from Yale University estimated that at 2006’s rate of global consumption, worldwide demand would outstrip the world’s supply by 2100. Other surveys estimate that there are at least 200 years of remaining copper reserves.

But these estimates don’t account for the reusability of copper, which doesn’t lose its quality after being recycled. In fact, during the last decade, 30% of the world’s copper needs were met with recycled materials. Copper supply is increasingly supplemented by recycled material, a trend that must continue if the world intends to rely on this mineral.

The Future of Copper

If these trends continue, what might we expect for the price of copper in the near future? The future of copper will likely be impacted by the following trends:

Sustainability

Across the globe, companies are pursuing a more sustainable future. For the mining industry, this means complying with regulations to mitigate pollution and other harmful effects.

Copper mining tends to release sulfur-containing waste material into the local ecosystem, contaminating nearby water supplies and producing acid rain. Mining operations in the developed world will increasingly tailor their operations to manage these hazards.

The problem, of course, is that as demands increase, production shifts to countries with volatile or hostile locales, such as the Congo or parts of the Middle East. This could present pressure from environmental groups seeking to retain regulatory control over the industry.

Renewable Energy and Electric Vehicles

Copper will be a major player as the world migrates toward renewable energy sources. Consider just a few of the following statistics:

- PV solar power systems contain 5.5 tons per megawatt

- Grid energy storage requires 3 to 4 tons per megawatt

- A single wind farm can contain anywhere from 4 to 15 million pounds of copper

Similarly, the electric vehicle revolution will produce new demands for the copper industry. A typical gasoline-powered vehicle contains approximately 55 lbs. of copper. An electric vehicle, by contrast, contains 183 lbs, and even a hybrid vehicle will contain 132 lbs. of copper.

This is to say nothing of the demand for new wiring configurations as American homes are outfitted to charge such vehicles. The fastest consumer-based chargers require a 220-volt connection, and many electrical contractors are already upgrading electrical panels to provide for this increased demand.

Globalization and Changes to the Supply Chain

In previous centuries, companies sought a monopoly over the copper industry. But in the years to come, the copper industry will rely on a broader network of smaller, independent producers with greater geographic distribution. This strategy will become all the more important as natural copper deposits continue to dwindle.

The obvious problem with this move toward a worldwide network is that the price of copper will now increase due to transportation costs from a network of mines to the factories and worksites that require it. This also raises the possibility of supply chain snags that can slow production, and shortages of copper (however temporary) could cause delays in the distribution of cars and other copper-intensive consumer products.

How Do Copper Prices Affect Our Products?

Since it can be shaped and molded without breaking or losing its tensile strength, copper is extremely popular as a metal for household items. There are many different household uses of copper, such as being used to create bathtubs, sinks, tables, and even range hoods. However, the price of copper can have a significant impact on our trade as well.

As manufacturers of copper products, the price of copper can play a role in how we price our products. For instance, a copper bathtub can cost several hundred dollars in terms of raw materials, and this must be factored into the costs of our products.

CopperSmith offers most products in a variety of 16 gauge metal or premium 14 gauge which is approximately 33% thicker, requiring even more raw material. The metal sourced for our products is hand forged from recycled copper by expert artisans. They're fantastic eco-conscious options for any customer that values sustainability.

Taking Labor Costs Into Account

In terms of profit margins, we have to take into account the cost of raw materials, the manufacturing costs, and also labor costs. A great example of this would be our artisan range hoods which are made by hand by specialists with years of experience. These products have fully customizable features; everything from the texture of the copper to the finish and rivets can be fully personalized to fit your kitchen.

As a result of this customization, the raw material cost is perhaps the least expensive factor when determining the cost of our products. The skill and expertise of our artisans, coupled with the many hours of hard work required to forge a bespoke product, make up the bulk of the cost of our products. Since all of our products are handmade, we can guarantee that each one is made with love and care to ensure longevity.

On the other hand, our copper tables are a different story. These products are still fully customizable, but they don’t come with the same complexities as our range hoods or bathtubs that require much more work. Our tables are hammered and wrapped over a solid piece of wood substrate to give them strength and durability. Since this is a rather simple process, our copper tables are much cheaper than our other products.

In short, the price of our products can vary a lot depending on how much manual labor is involved in its creation. The price of the raw copper material might be only a fraction of the cost of the final product, and this is because of the amount of labor required to forge something bespoke.

How Copper Quality Can Affect Pricing

Fluctuating copper prices can often force some manufacturers to raise their prices, but the more common alternative is to maintain the same prices (and thus profit margins) by lowering the quality of the product. For instance, a manufacturer or designer may use low-quality copper that is structurally weaker or has less thickness, resulting in an inferior product.

However, This isn’t the case for CopperSmith. All of our products range from 15 gauge to 17 gauge thickness, giving our products plenty of durability depending on the intended use case. This is also customizable by the end user.

Copper quality makes a huge difference in the look and feel of the final product. With our products, we typically use recycled copper to create a rustic finish. This is not just for stylistic choices. We forge our own copper to ensure that we can maintain a consistent level of quality across all of our products.

High-quality copper is not only structurally superior to low quality copper, but it also creates a natural and authentic beauty for your home. We stick to our roots to express our love for old-world artisan techniques. This highlights not only our craftsmanship but the natural beauty and structural quality of copper.

CopperSmith also makes use of virgin copper which is mined directly from the earth. It’s typically used for electrical wiring and coin production but is also used for decorative items. Virgin copper creates a beautiful modern, shiny penny finish on some of our products.So regardless if you’re buying a copper sink, bathtub, or range hoods, CopperSmith guarantees the same level of consistent copper quality as we do for all of our products.

Will Copper Go to Infinity (and Beyond?)

In 1982, an almost unnoticed change occurred. The penny, once composed almost entirely of copper, was to be henceforth composed of zinc with a thin copper coating. The reason, of course, was due to rising costs. Ironically, a penny costs more to make than it’s actually worth.

Is the copper industry headed for a similar fate? Such widespread consumption has caused some industry analysts to wring their hands regarding the future of the global copper supply.

But new discoveries are being made all the time. Between 1975 and 2005, 56 new copper sources were discovered. And between 1996 and 2013, the global copper reserve increased from 310 million metric tons to 690 million metric tons.

New mining techniques will continue to enable copper producers to extract copper of varying degrees of quality, vastly increasing the efficiency of the copper industry. Similarly, recycling programs have the promise to allow copper production to continue indefinitely. An estimated 80% of the world’s copper supply is still in use, showing the longevity of this resource.

Copper is here to stay. They compose the wires that bind society together in a digital landscape, and they just may pave the way for our future. Check out the copper patina guide if you're looking for more info on copper.